Crabs. In

Part I, we talked about their personalities. Now this may seem frivilous, but as it turns out, the key to catching crabs is understanding what motivates them.

In a word: GREED.

They are not wily. They are not shy. They are not subtle. So, to catch them, you don't need to be any of these things either. You just cater to their greed.

In Puget Sound, you will see two primary tools in use for catching crab. The simplest and cheapest is the crab ring. Now, that is kind of a misnomer, since the crab ring is actually

two metal rings, a smaller one and a larger one, linked with netting. When dropped onto the bottom, it lays flat, but when hoisted up, it forms kind of a net bucket. It is attached to the line by a three-legged harness which should have a float on it so that when the ring is dropped into the water, it lands right-side up.

How is the ring used, you might ask (if you've read this far)? It is simplicity itself. You tie the bait securely to the netting inside the smaller ring, and throw it in the water. Wait 20-30 minutes (or maybe a little longer for the first pull), and then retrieve it. Bait? There are lots of suggestions here, but we have found that a turkey wing or drumstick neatly fits into the intersection of cheap, easily available, easy to attach securely and satisfying crabs' greed. Now, that's twice I have said it: Tie the thing on securely, or a crab will haul it off. They are not weaklings... you will sometimes find that they have broken the bone in the drumstick. After a couple of hours, the best of the juices will have been leached from the drumstick, and the crabs will no longer be able to smell it as well in the current. If you don't have enough for dinner yet, you will probably want to replace the bait.

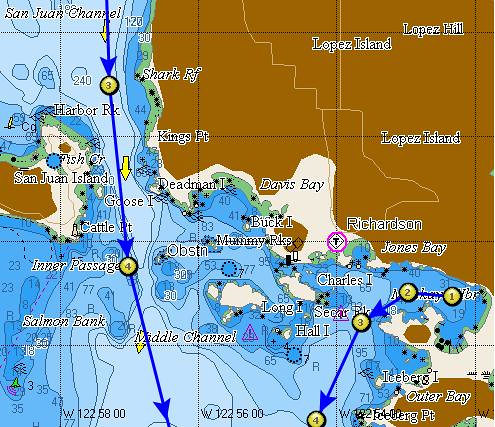

But, if you don't have enough for dinner after a couple of hours, you should probably try a different spot. Which brings up the second question: Where to put the ring? Eating-sized crabs prefer deeper water - say 30-50 feet. But that's the ideal. We like to just crab off the boat while we are at anchor. In some places (Port Madison, for example), it doesn't pay because the water is so shallow - all you get are babies. When crabbing off the boat at anchor, be sure to veer enough line so that the boat tacking back and forth on the anchor doesn't drag the ring all over the bottom. Oh, and Jane says she has better luck on an incoming tide.

The other device in use on Puget Sound is a crab trap. These are (usually) steel mesh enclosures with little flaps that the crabs can open to get in, but can't open from the inside. These are set-and-forget devices. You bait them and put them over the side in a likely place, coming back hours later to retrieve your catch. Since these are left unattended, there are rules for the kind of float used to mark them on the surface, and the kind of line used to attach the float to the trap. Knowledgeable crab trappers tie the bait to the inside of the

top surface of the trap, or use a bait box.

Whichever device you use, you are eventually going to bring it up, full of crabs. Now what?

First, you can't keep everything you catch. There are size limits, and they really do make sense. Anything smaller than the allowable limit is going to be too small to bother with eating anyway. Second, for Dungeness crabs anyway (that's what these in the picture are), you cannot keep females. The overturned crab in the picture is a male - see that triangular-shaped plate on his belly? On a female, this plate is much wider and kind of rounded. For the other kind of crab commonly caught in Puget Sound, the Red Rock crab, the size limits are different and you can keep either sex. They are easy to distinguish from the Dungeness, because they are more stretched out side-to-side, and because they are, umm... red.

Whether you are going to keep them or throw them back, you have to get them out of the netting or the trap. This can be kind of tricky for the uninitiated. When you reach for a crab, you will quickly see how aggressive they are. They will rear back and wave their claws at you, trying to clamp on. The only safe way to grab a crab is from the back - and they know this, so they will try to prevent you from doing it. If you can turn the crab onto his back, he will shortly and magically go passive - like the one in the picture. Then they are easy to grab from the back. If you continue to hold them upside down, they will stay passive, like the two live Rock crabs I am holding in the

picture in the part I post. You must work quickly - they will soon be scrabbling all over the deck, going every which way.

Now, I am going to leave you, holding that crab upside down from the back, until the final installment, where I will take you to that final messy joy of cracking and eating crab.

Don't let him go.

Crabs, Part 2: How to get 'em