This is a guest column written by my friend Erick over at Erick's Wanderlust Blog, and reprinted here with his permission. See the original at Expensive Weekend: Lessons Learned

I wanted to take my parents out to the boat for a post-Christmas sail this previous Saturday. They have seen and been on

Windsong, but haven't been out for a ride yet. I had been following the weather conditions for Saturday all week and it looked to be a great day for sailing with 15 knot winds out of the North. That would allow us to beam reach all the way out of the channel so we could start sailing before we even got to the final channel marker. The only issue I really saw was that it would be a chilly day (for us Floridians) with highs in the 50's. High tide would be in the morning when we would head out, but we would have to come back at low tide. However, it would be a +1 foot low tide, which I was told would be deep enough for

Windsong to make it through the river with.

I typically have gotten nervous when it comes to taking

Windsong out, rightfully so I might add. I am still a rookie with this boat and particularly the area it is in. Especially after breaking down the first time I took her out, I can't help get nervous. But this time I wasn't worried about the engine or anything particular about the boat. I've tuned the engine and performed all needed maintenance on it and it worked like a charm the last outing. But something was eating away inside me the few days leading up to Saturday and I didn't understand it. Some sort of premonition told me it we shouldn't go, but I ignored it and attributed it to my normal nerves. I should have listened.

So we took the 3 hour ride from St. Augustine to Inglis with my parents and their new Boston Terrier pup, Sawx. As we arrived to the dock my nerves had subsided and was ready for a good ride. I performed all the pre-ride checks on the boat and engine and felt pretty confident that

Windsong would do well. Shortly after arriving we cast of the docklines and headed up the river towards the Gulf.

Things were going swell all the way up the river, so good in fact that I must have stopped paying much attention to where I was in the channel. We were motoring at roughly 6 knots only a few hundred yards before we reached the inlet when the boat SLAMMED into the river bottom and the bow reared up high out of the water. Thank goodness that no one was standing at the time or they would have gone flying off the boat or hard into something on it. I tried reversing and steering off, but we were stuck as stuck could be. The keel was resting hard on the bottom and would not budge. I sat there shocked and stunned and could not believe what had just happened. I took a moment to collect myself and made sure everyone was ok before I could think of what to do next. I considered kedging off the anchor but I had no way of getting it out far enough to be worthwhile. So I radioed on channel 16 for some help but recieved no ansewer even after a few tries. I eventually called the Coast Guard, which has a station on the river near the boat's dock, and told them my situation. They said that the only thing they could do is refer me to a towing company either Tow BoatUS or Sea Tow. I knew instantly that this was going to be a worse incident than I thought when they asked if I was a member to either. No, I'm not.

For somewhere around $150/year you can be a member of one of these tow companies and use their services when you need. I had considered getting a membership in particular for the overnight passage South that I need to take soon, just as a piece of mind in case things went wrong. But I never figured I would really need it until I finish working on the hard and start to sail a lot. I realized that was that a huge mistake as I spoke to the tow boat captain and got a quote to be hauled off the bottom. It would be $600 just for ungrounding the boat, plus $240/hour for the tow boat to come from Cyrstal River, about an hour and a half away ( you have to pay for their round trip). So the total quote for the haul was roughly $1,300. When he told me this all I could do was close my eyes, swallow my pride and gave him the ok to come get me. Bye Bye huge hunk of savings.

I considered my options while I waited for confirmation on my credit card and everything. We could wait for a boat to come by and hopefully lift us off with their wake. Unfortunately it was a very quiet day on the river and the only boats going by were small jon-boats with barely any wake. When a decent sized boat finally passed and sent wake our way, it only served to bounce the keel up and down on the bottom, not freeing us at all. Since we ran aground near high tide, it was apparent that waiting for the tide to come back in wasn't going to help much either. Plus, high tide wasn't until 8 p.m. and we had no way of getting back to the dock at night. Navigating the river without light was just out of the question.

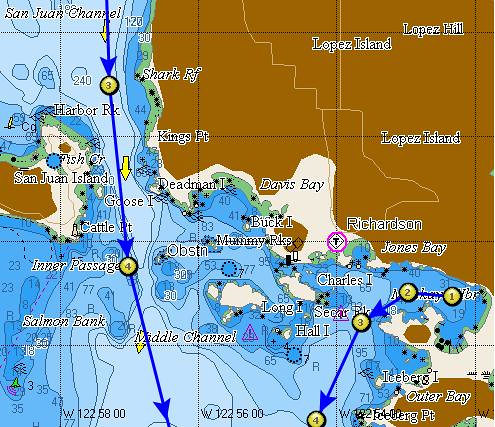

So after a few minutes the tow company called me back and confirmed the operation and told me they would be here in an hour and a half. Great, by then the tide would be even lower and getting towed off the bottom would be even more difficult. So we sat waiting for that period of time, during which the air only seeming to get colder by the minute. I was so pissed that I made such a bonehead move that I could do little but stare at the distance in disdain for my bad piloting. But how would I have known this ledge was here? It wasn't marked on the charts or on my new GPS as most obstructions were in the river. As some fishing jon-boats rode by and we discussed what happened they all seemed to know that it got shallow there...local knowledge kicks ass if you have it, but I didn't.

I started to fear about the worst case scenario as the tide began to fall. On the port side, closest to shore, we could see that the water was getting shallower pretty quickly as the bottom was clearly visible in the murky water. On the other hand, the water to starboard was much deeper, if only we could get to it. The tow captain mentioned that if he didn't have success trying to pull us off since the tide was too low we would have to wait for it to come back in before trying again. Thus having to wait till all light was gone and we would be stranded there for the night. We were horribly unprepared to stay the night on the boat particularly due to the cold. We had food to last us, but no blankets and barely enough jackets as it was. I know my dad and I could tough it out if we had to, but my mom and the pup were with us and I would feel horrible if she had to go through that. So I thought if worse came to worse, the tow boat could take my parents and the dog back to the dock and I would stay with the boat overnight and wait for the morning high tide. Still, not something I was looking forward to as my first overnight stay on the boat. I would have been left with little more than sail covers as blankets to not freeze the whole night away.

The tow boat showed up right on queue and rafted up next to us. They sounded the area and found the water deep enough for my draft immediately to starboard, so not all hope was lost. But the water had gotten so shallow on the port side that if any of us put our weight over there the whole boat tilted on its keel at a hard angle. So we tied up the tow ropes and they started trying to pull the bow towards the center of the channel. It didn't work too well and only turned the boat a bit towards the channel, grinding the keel on the bottom. At one point the tow rope snapped after pulling so hard.

Things didn't look to bright at this point and the tow captain kept mentioning about possibly having to wait till high tide, my heart kept dropping as the effort kept failing. Eventually we tried a new tactic by using the main halyard attached to a second tow rope (leads to the top of the mast) to try to tilt the whole boat on its side, thus lifting the keel off the bottom as the tow line on the bow would pull the boat to the channel. After much grinding on the bottom and tilting the whole boat so far that the starboard rail was buried under water, it finally got loose off the bottom and we were pulled into deeper water. It took a long time and many different tries at different angles, but we eventually were pulled free. It was incredibly nerve wracking as it seemed like it would never work.

Relief rushed through me and I could do little more than thank God it was all over and we wouldn't have to stay there any longer. I made sure to ask the captain where else in the river I needed to be wary of, and he said that where we went aground was the worst spot. He has apparently pulled many a vessel off of the same ledge, one even a week previous. Good to know I thought, I will avoid that spot like the plague for now on.

The tow captain was friendly and also owns a sailboat. He told me to not get discouraged since pretty much everyone has made that mistake. Unfortunately I made the double mistake of not being a tow member and having to loose a big gob of cash. On top of it all, my brand new hand held VHF radio was clipped to my belt and sometime during the tow when the boat was heeled over and I was holding on for dear life, it got loose and went overboard. I was concentrating on the job at hand and none of us noticed it until we were motoring back to the dock. So the day got even more expensive.

It was a very bad day for me, but I was more relieved than bitter in the end and was glad we got back safely before dark. I felt pretty bad that we took the long drive out there to only have a bad experience, but my parents were positive the whole time and gave me good encouragement. It was a rough lesson learned, but one I was bound to learn one day nonetheless.

Years ago when I was a kid, I used to read Flying magazine. I particularly enjoyed a long-running series of articles entitled "I Learned About Flying From That." Each article was written by a pilot, who humbly admitted to having made a mistake, and then having lived, told about it in the hopes that others would not have to make the same mistake. I thought then that it was a good format, and I still think that now. This series of postings is my attempt to recreate that article series with a new subject and new technology.

(If you would like to help others to learn from your mistakes, please send your article to: WindborneInPugetSound at gmail dot com)

I learned about sailing from that: Running aground